Clyfford Still’s Figures Run Deep

Clyfford Still manipulated his own history. He reacquired and destroyed early canvases, removed titles from his paintings, and, at the height of his fame, refused to allow exhibitions of his work. Control was even more rigorous after his death. His estate, consisting of 825 paintings and 1,575 works on paper—94 percent of his entire output—was sequestered from the time of his death, in 1980, until the opening of the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver last year. Now, hundreds of examples of Still’s art from the mid-1920s to the late 1970s are accessible at the museum, together with his comprehensive archive. Shadowy corners in his artistic evolution are being illuminated.

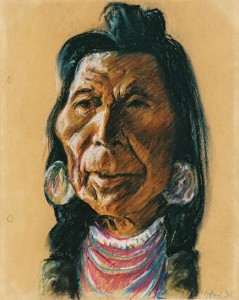

PP-241, 1936, one of Still’s drawings of native peoples on the Colville Reservation in Washington State. GARY REGESTER/©CLYFFORD STILL ESTATE/COURTESY CLYFFORD STILL MUSEUM, DENVER

The museum’s inaugural exhibition in 2011 presented a survey of Still’s works from 1925 to the late 1970s; 50 new paintings and 20 new drawings were installed for a second exhibition this summer. This month, the museum released its first substantial catalogue of Still’s work, Clyfford Still: The Artist’s Museum, with commentary by Still scholar David Anfam, the museum’s adjunct curator.

Reviewing scores of previously unknown paintings, drawings, letters, and photographs, according to Anfam, has been “akin to unearthing an artistic time capsule from another century. . . . Overall, some sixty years of activity prevail here, without extraneous distractions, in a single site. In effect, the panoply also doubles as a life told in the round through the medium of art.”

Anfam and museum director Dean Sobel agree that the collection’s most significant revelation so far is the debt Still’s abstractions owe “to a temperament deeply versed in figurative habits,” as Anfam puts it. Unlike his colleagues Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, Still developed a command of traditional drawing skills early in his career.

“I’ve long suspected a figurative substratum lurking in his abstractions,” Anfam observes, “and now I’m convinced. What we get with Still is a productive fusion of a draftsman with a good empirical eye for catching forms and outlines, but also a very, very powerful symbolic imagination. It’s the fusion—or, really, the collision—of these two qualities that seems to be responsible for so much of what is distinctive about his work.”

Still’s aptitude as a draftsman was overshadowed in part because he rarely displayed his representational drawings, and also because, by the mid-’40s, the representational forms in his early paintings were powerfully refigured in jagged flashes of pigment and textured surfaces. As art historian Richard Shiff points out, “figure” can refer to a representational image, but the concept also relates to metaphor, as in “a figure of speech.” To figure or refigure is to apprehend or make sense of something through something else, playing one kind of knowing against another. The Still Museum collection reveals, in effect, the trajectory of Still’s creative struggle to transform his “figurative habits” from the first to the second sense of the term.

Anfam summarizes the result: Still’s early preoccupation with “arid earth, hot suns, bloody hands and benighted lives,” he says, “becomes transfigured in his final three-and-a-half decades into a visual poetry of drought and fire, luminosity and obscurity.”

Despite the wealth of new visual evidence, tracking the progression of Still’s artistic development often challenges even the experts. A case in point is the museum’s cache of previously unknown or little-known drawings related to Still’s tenure as an instructor at the Nespelem Art Colony, established on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington in 1937 and active until 1941. According to historian J.J. Creighton, Still was a founder of the colony, together with Worth Griffin, his faculty colleague at Washington State College (now Western Washington University).

Still envisioned the colony as an outpost among the regionalist art centers set up in the mid-’30s to support “authentically American” art forms. Nespelem, Still wrote, “might form the nucleus of what could readily prove to be a vital, creative art movement in eastern Washington comparable to those developed in Kansas, Iowa, Texas, Oklahoma and many other places.”

Twelve different Native American tribes inhabit the Colville Reservation, located near the Grand Coulee Dam, which was under construction when Nespelem was founded. The colony’s purpose was to create a visual record of what was popularly believed to be a vanishing culture. The painter Ruth Kelsey, who later became an art instructor at Western Washington University, remembers Still as a patient, considerate, and tolerant teacher who isolated himself from students and instructors when he painted. Still did not acknowledge his tenure at the colony in later memoirs, however, and his drawings of tribal life on the reservation all date from 1936, the year before the colony was established.

Gaps in the historical record aside, assessing the impact of Still’s experiences at the reservation on his later paintings remains contentious. An influential study by art historian Stephen Polcari finds imagery in Still’s early 1940s abstractions modeled from Native American war clubs and other ritual objects. Anfam sees Still’s contacts with the Colville tribes as playing into his earlier preoccupations with totemism and animism, and he dismisses the possibility of mimetic correspondences between Still’s abstract forms and “the clubs, thunderbirds . . . or umpteen other tribal items they might resemble.” Anfam asserts, nevertheless, that Still’s contact with the reservation encouraged him to “adopt the mantle of a latter-day shaman, opposed to the corrupt decadence he perceived in Western society.”

Squaring such interpretations with the museum’s new hoard of visual evidence is a complex venture. With the exception of a few portraits, most of Still’s Native American scenes are relatively generic, picturesque, and stylistically consistent with other paintings and drawings produced by students and his faculty colleagues at the colony. Anfam attributes the relative sweetness of the drawings to Still’s sympathy with his subjects and his understanding of their bond with the earth, the source of “reparative energies to countermand a damned or fallen world” depicted in the artist’s other paintings of the mid- and late 1930s. He also connects the bright lilac, crimson, golden-yellow, and leaf-green color accents in Still’s drawings to a “colorism already kindled by van Gogh.”

Still railed for years against the decadence of European artists and insisted that he was not influenced by anyone. Nevertheless, Anfam makes a strong case for a deep kinship between Still and the Dutch painter, even suggesting that the young Still’s decision to sign his artworks with only his first name mimicked “a predecessor whose imprimatur was ‘Vincent.’” He also offers evidence that Still deeply admired and was influenced by other Europeans, including Rembrandt, Turner, pre-Cubist Picasso, and Cézanne, the subject of Still’s 1935 master’s thesis.

Still insisted on a posthumous repository where his art, library, and personal papers could be studied as an organic body. As Anfam’s discoveries demonstrate, Still’s goal may have been to take personal responsibility even for his apparent contradictions and to demonstrate, as he wrote in 1951, that “I am not, nor will not, conceive myself to be a sum of parts. I say that I am, and will reinforce that point by stating every phase of that identity to the fullest extent possible.”

New analyses of Still’s early work—the “figurative substratum” of his abstractions—have been given the most weight in the museum’s opening exhibitions and new catalogue, but admirers of Still’s art will undoubtedly welcome an equally intense focus on other dimensions of his mature canvases. What was Still thinking, for example, when he painted his “replicas”—close copies of earlier abstractions? Still regarded these compositions as “occasions to clarify or refine a specific work” as well as “valid and totally individual expressions.” As Sobel has recently discovered, at times Still created new abstractions by cutting away fragments from a larger canvas, including fragments of a replica.

Even if the Still Museum collection represents, as Anfam believes, a “veritable autobiography in paint,” such practices suggest that Clyfford Still is likely to confound even his closest readers for a long, long time.

By Patricia Failing

Source: www.artnews.com

Patricia Failing, a contributing editor of ARTnews, is a professor of art history at the University of Washington, Seattle.