From the archive, 9 April 1973: Picasso, end of a dynasty

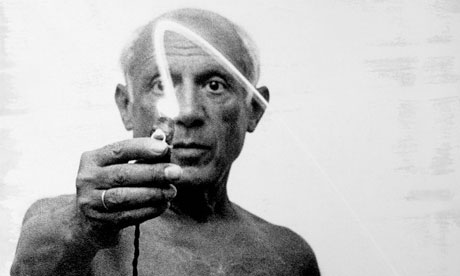

Artist Pablo Picasso using flashlight to begin making light drawing in the air. Photograph: Gjon Mili/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

In a real sense, Pablo Picasso was the last Renaissance man: an artist who was universally revered (and reviled). He was a beneficiary of the fame of Michelangelo, who shattered the bondage of the artist’s subservience, but also of modern communications which made his merest doodle better known than any of Michelangelo’s. He was hugely prolific and his genius left its imprint everywhere. His influence can never be precisely stated, but the world would look different had his cradle not rocked in Barcelona twenty years before the new century dawned: architecture, sculpture, theatre design, poster design – the whole man-made environment – basked in the sun king’s light.

But Picasso was the end of a dynasty as well. After the first, fine, careless rapture of cubism, art lost its absolute certainties. Picasso himself made an immense fortune and subsidiary industries like monographs of him and films about him and forgeries of his work all flourished.

But painting itself stumbled into a decline from which it has not recovered. After Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Leger, the French School became dismal and insipid, and nothing – certainly not New York – has replaced it. Picasso’s own financial success was a standing mockery to younger painters: the giddy whirl of publicity and cash seems to many young artists an insult to their calling. It is not to the abundant creativity of Picasso that artists turn now, but increasingly to the mocking gestures and iconoclasm of Marcel Duchamp.

Picasso himself can hardly be blamed for this. His social attitudes may not have been as important or as influential as his art, but they were consistent. He painted “Guernica” as a protest against the Civil War atrocity, and to the end of his life he refused to return to his native land.

He made money merely by lifting a little finger dipped in ink, but he was a Communist who longed, naively no doubt, for the classless society. His painting destroyed the old way of looking at things, but the movement was already under way and would have gone ahead without him. The Impressionists, Gauguin, Matisse and Fauves, Kandinsky, the artists of revolutionary Russia had pushed art away, not just from Renaissance perspective, but from imitation. The reaction could be healthy. Young artists tend less and less to want to starve in garrets (as even Picasso did for a while) or to see themselves as lonely eminences. La vie Boheme has been replaced by the desire to be closely involved in society. The rest of society has not readily appreciated this, and the reverberations in this country alone of the art school troubles at Hornsey and Guildford will not die away yet awhile.

Creativity has not died with Picasso, but painting itself is at a low ebb. The issue everywhere now is: how do we channel the energies of young artists and students?

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk