‘Picasso Black and White’ at the Guggenheim Museum

You might expect “Picasso Black and White,” at the Guggenheim, to feel like a glamorous gimmick — the museum-blockbuster version of Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball.

2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Gassull Fotografia, via Museu Picasso, Barcelona. The first of Picasso’s variations on “Las Meninas,” inspired by Velázquez, is on loan from the Museu Picasso Barcelona.

Happily the exhibition, billed as the first monochromatic look at Picasso’s whole career, is much more than a clever conceit. It’s as eye-opening as it is elegant, especially among the later works on the upper ramps, which push well past the obligatory Neo-Classicism and Analytic Cubism into bracingly sensual explorations of the figure, strident political cries de coeur à la Guernica, and winking homages to Delacroix and Velázquez.

“Picasso Black and White” is, furthermore, a refreshing change from the parade of shows about Picasso’s relationships with women (as in Gagosian’s recent series of exhibitions) or with other artists (“Matisse/Picasso,” “Picasso and American Art,” “Picasso and the Avant-Garde in Paris”). Here there is just Picasso, stripped down and essentialized, his classical lines and radical sense of painting as sculpture both heightened by the restricted palette.

And in places that palette is more liberating than limiting. As Gertrude Stein put it, “There is infinite variety of gray in these pictures, and by the vitality of painting the grays really become color.” She was talking about Picasso’s early gray still lifes, but her words could easily describe later works like “Marie-Thérèse, Face and Profile” (1931), a portrait of the young and pliant muse we know from bold-hued paintings like “Le Rêve.”

Also extraordinary: the vast majority of the show’s works are private loans, about half of them secured from the Picasso family in what is certainly a remarkable feat by the show’s curator, Carmen Giménez. (Ms. Giménez, the museum’s curator of 20th-century art and a former director of the Museu Picasso Malaga, organized the show with help from the associate curator Karole Vail.) Thirty-eight of the show’s 118 works have never been exhibited in this country, and 5, among them the sharply angular “Bust of a Woman With a Hat” (1939) have never been seen anywhere in public.

2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, David Heald, via Koons Collectio. "The Kiss," a Picasso work from 1969.

The implication is that we are seeing a more personal side of Picasso in his black-and-white paintings, most of which, Ms. Giménez suggests in the catalog, have wound up in the hands of the family and the Musée National Picasso in Paris because the artist was unwilling to part with them.

The few loans from other museums do not disappoint. They include “The Milliner’s Workshop” from the Pompidou in Paris; the first of Picasso’s variations on “Las Meninas,” from the Museu Picasso Barcelona; and three studies for “Guernica” from Reina Sofía in Madrid. Together these works support a theory, voiced by the critic David Sylvester, that Picasso often turned to black and white in his busier, more ambitious paintings. It was his elegant solution to crowded compositions, “just as the reduction of color to grisaille in Analytic Cubism resulted from the pressure of its intricate problems of form.”

“Picasso Black and White” puts forth other ideas about his reasons for paring down his palette, as he did on and off over his career. He had Blue and Rose periods but nothing resembling a “black-and-white period,” as Ms. Giménez reminds us. Or, as the photographer Brassai observed, he had several black-and-white periods: “A period of painting on a flat surface with a bright and varied palette was regularly followed by a sculptural period with little color.”

One possible motivation for these colorless phases concerns the centuries-old tradition of grisaille, a form of gray or brown tonal painting. Often it was meant to create the illusion of sculpture, as works like Picasso’s “Bust of a Woman, Arms Raised” (1922) seem to do. (A valuable lesson of this show is that Picasso’s interest in fusing painting and sculpture did not begin and end with Cubism.)

The black-and-white paintings may also owe something to ancient history, namely the Paleolithic cave paintings that Picasso is known to have visited and admired. The figures in “The Lovers” (1923), for instance, are thickly outlined on a brushy gray ground that could pass for limestone.

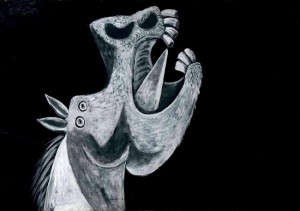

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Bequest of the artist, 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Picasso's “Head of a Horse, Sketch for Guernica," at the Guggenheim Museum.

You might also see, in parts of the show, a less classic and more contemporary Picasso — an artist who used a black-and-white palette because he saw it everywhere, in newsreels and newspapers and images in art books. Looking at “The Milliner’s Workshop” (1926), with its interlocked biomorphic forms in many shades of gray, you have the uncanny sense that you are looking at a black-and-white reproduction of a colorful abstract painting.

The obvious explanation, however, is the show’s most haunting one: that Picasso used black and white to reconnect to his Spanish heritage. This is clear from the Guernica studies and the Velázquez-inspired “Meninas,” of course, but also from the series of seated women that he painted in Nazi-occupied Paris in the 1940s. They may have teeth on the sides of their heads and eyes that stare in different directions, but they are, unmistakably, heiresses to Goya’s gray ladies.

The experience of “Guernica” seems to have intensified Picasso’s black-and-white painting. His large narrative works, like the “Rape of the Sabines” (1962), reveal an expanded tonal range, with high contrast reserved for areas of particular urgency. And in smaller paintings like the vanitas-themed “Skulls,” the grays thicken to thundercloud density.

Inevitably “Picasso Black and White” is also a judgment on Picasso the colorist, repackaging a long-held criticism — that he was indifferent to or indiscriminate with color — as a virtue. “The fact that in one of my paintings there is a certain spot of red isn’t the essential part of the painting,” Picasso himself once said to Françoise Gilot. “You could take the red away, and there would always be the painting.”

The Guggenheim has put Picasso’s words to the test, filtering color out of the picture entirely. And, just as he promised, the painting is still there.

By Karen Rosenberg

Source: http://www.nytimes.com