Polynesian objects were given equal status with Gauguin’s work in a groundbreaking and subversive exhibition

Paul Gauguin died a pauper on the Marquesan island of Hiva Oa in 1903 and was buried in an unrecorded grave. In 1921 local residents picked a site in the island’s old cemetery to serve as the artist’s burial place, and in 1973 it was embellished with a replica of Gauguin’s sculpture of the Tahitian goddess Oviri. The “grave” is now a major tourist attraction on the island.

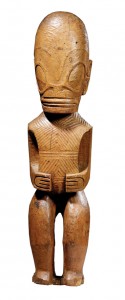

Tiki, 19th century, from the Marquesas Islands. COLLECTION MUSÉE DE LA CASTRE, CANNES

Gauguin’s fictive resting place tidies up his biographical story, but there is no corresponding order in recent debates about the facts and fantasies that inspired his South Sea paintings. A new and potentially subversive argument about the interplay between the paintings and island cultures was offered this spring in the Seattle Art Museum’s exhibition “Gauguin and Polynesia.” Organized by the Art Centre Basel and conceived by a team of specialists in European and Oceanic art, the show was designed to “bring Gauguin’s paintings and sculptures face to face with a large number of Polynesian cult and art objects.” The Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen premiered the exhibition, and Seattle was its only venue in the United States.

“Gauguin and Polynesia” played against two other recent exhibitions: “Gauguin Tahiti,” organized by the Grand Palais, Paris, and hosted by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2004, and “Gauguin: Maker of Myth,” organized by the Tate Modern, London, and shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 2011.

The Paris exhibition analyzed the European “ancestors and progeny” of the Boston museum’s celebrated painting Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? (1897–98). “Gauguin: Maker of Myth” examined rhetorical constructions supporting “the Gauguin phenomenon,” including the artist’s own self-fashioning in portraits and writing.

In his essay for the “Gauguin and Polynesia” catalogue, Musée d’Orsay curator Stéphane Guégan is critical of both the Paris and London exhibitions. He believes that the Paris show overplayed the artist’s disenchantment with Tahitian life and culture, while the London show, in his view, was conceived by art historians who regard Gauguin as a cheat and inveterate liar. Guégan’s reservations about these earlier exhibitions, however, ultimately center on their neglect of Gauguin’s serious intention, in Guégan’s view, to investigate Oceania as “a terrain of anthropological as much as aesthetic research.”

The seriousness of Gauguin’s commitment to anthropological research is a subtext addressed directly and, by implication, in the catalogue and display strategies devised for the Seattle exhibition. In contrast to earlier shows, in which Polynesian artworks were typically presented as visual background for Gauguin’s development as a modern European painter, the goal in Seattle was to place these objects “at the heart of the exhibition.”

The curators presented scores of 18th- and 19th-century Polynesian sculptures, carved bowls, head ornaments, war clubs, fans, drums, and canoe models in a central gallery, prefaced and followed by galleries filled with an equal number of Gauguin’s paintings, prints, sculptures, and drawings. Visually, this strategy was a great success: the sophisticated and elegantly crafted Polynesian objects asserted themselves as powerful counterpoints to the paintings, which appeared as somewhat repetitious and formulaic in the final galleries.

The show’s visual argument, however, was uneasy and potentially misleading. Gauguin could not have seen many of these Polynesian objects, nor could he have known their meaning and function. By the middle of the 19th century, Christian missionaries in Tahiti had outlawed native cultural practices such as carving, tattooing, and dancing, and there was relatively little traditional art to be found in Tahiti when Gauguin arrived, in 1891. When he moved to the Marquesas, in 1901, the islands were depopulated, and traditional cultural practices for which many of the artifacts on display were created had disappeared. In Tahiti Gauguin did find late-19th-century Marquesan carvings made for the tourist trade, and he studied major examples of traditional Maori art during a short stay in New Zealand in 1895. The effect these objects and their histories might have had on his paintings, however, becomes an even more ambiguous question in the catalogue essays than in the exhibition’s visual display.

In the first essay, one of the show’s organizers, Suzanne Greub, tells us that “Polynesian works of art served Gauguin more as symbols and decorative accessories and less as influences on his style. Such references, in a few paintings and some sculptures, occur more rarely and often more incidentally than his allusions to non-Western courtly forms such as those of Egypt, Persia and especially Cambodia and Java.” Illuminating essays on Marquesan art and culture by Carol Ivory and Marie-Noelle Ottino-Garanger, specialists in Oceanic art, barely mention Gauguin, suggesting that, from a specialist’s vantage point, Gauguin and the Polynesian colonies he inhabited did not profoundly intersect.

Could these texts signal a subplot for this project? The form and content of the exhibition do in fact suggest that—probably for the first time—Gauguin’s mythology has been successfully leveraged to support a substantial exhibition of Polynesian art.

If so, the exhibition becomes a functional analogue to Gauguin’s grave, a lure with benefits, including an opportunity to experience the case Polynesian visual culture can make for itself, on its own terms, and not just as source material for Gauguin’s seductive dreams.

By Patricia Failing

Source: www.artnews.com

Patricia Failing is an ARTnews contributing editor.

Copyright 2012, ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th St 9th FL NY NY 10018. All rights reserved.