The Peabody Essex Museum Presents Largest Native American Art Exhibition for More than 30 Years

Salem, Massachusetts.- The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) is proud to present “Shapeshifting”, on view at the museum from January 14th through April 29th 2012. “Shapeshifting” is one of the largest Native American Art exhibitions to open in North America in more than 30 years and includes nearly 80 works from public and private collections worldwide offering a far-reaching exploration of Native American art as a continuum, juxtaposing historic and contemporary artworks. Through constellations of objects created in a range of media – sculpture, painting, ceramics, textiles, photography, drawing, film, video and monumental installation – visual and conceptual connections are drawn between generations of Native people, art traditions and cultures. Spanning vast cultural, historical, intellectual, and aesthetic terrain, “Shapeshifting” offers a new approach to Native American art by exploring the conceptual underpinnings and artistic intent of contemporary and historic artworks alike.

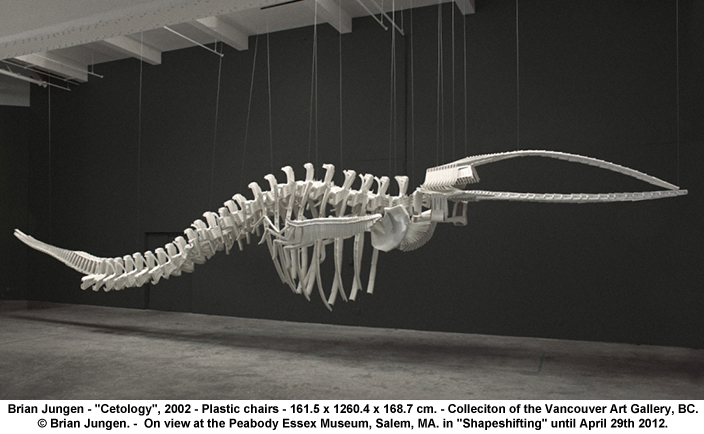

“We have been especially fortunate to have the wise counsel, creativity, and expertise of a stellar group of advisors, authors, and artists from a wide range of disciplines and experiences, including many from Native American and other cultures,” said Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, The James B. and Mary Lou Hawkes Chief Curator at PEM. “Shapeshifting” is organized into four thematic sections: Changing, Knowing, Locating, and Voicing. Two monumental contemporary installations that compellingly address familiar icons and materials – Kent Monkman’s 2007 “Théâtre de Cristal” and Brian Jungen’s 2002 “Cetology” -begin and end visitors’ journey through the exhibition. Native artists have continuously embraced innovation, adapting new ideas and expanding their means of expression. Nicholas Galanin’s 2006 video work, “Tsu Heidei Shugaxtutaan (We Will Again Open This Container of Wisdom That Has Been Left in Our Care)”, powerfully conveys the artist’s ability to overlay his experiences as a Native American in contemporary society with the cultural traditions of his Tlingit and Aleut ancestry. His two-part video begins with a non-Native break dancer in an empty industrial space performing modern dance moves to the chant and drum of a traditional Tlingit song. The second portion is a perfect inversion: a Tlingit dancer in full ceremonial garb performs a traditional dance to the beat of electro-bass techno against the backdrop of Tlingit carving motifs.

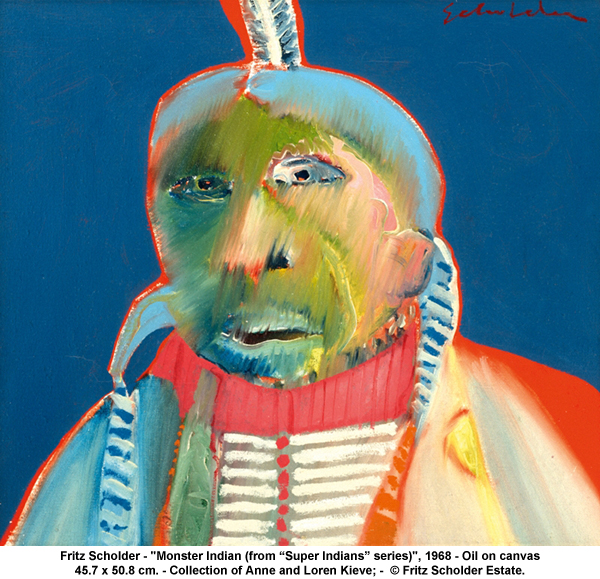

The second gallery illustrates the strikingly different ways in which artists imagine, understand and express their experience in the world, especially as influenced by culture and unique personal vision. It is intended to counter the perception that Native people share a single monolithic worldview. The upper portion of a Yup’ik ceremonial mask from the early 1900s depicts walaunuk, the movement of bubbles rising to the surface of water. Among the Yup’ik of Alaska, bubbles are considered to be visible manifestations of breath and underwater life. A seal, for example, must willingly give up its life to a hunter and, when doing so, the animal’s soul retreats to its bladder. In reciprocity for this sacrifice, Yup’ik men inflate seal bladders during a five-day winter festival. At the close of the festival, the seal bladders are deflated under the ice, returning the animal’s spirit back to the water. As in many cultures, the haunting question of ‘where is home?’ is undeniably formative. The third section of the exhibition considers the importance of family, community, land, and place in the cultivation of Native individual and tribal identity. Kevin Pourier’s 2008 Sitting Bull Spoon revives the creative use of buffalo horn by 19th-century Lakota people. While wild buffalo populations have been largely decimated and few contemporary artists work in this medium, Pourier has taken the traditional practice of buffalo horn carving and has created something quite modern. An image of the legendary Hunkpapa Lakota leader, Sitting Bull, is painstaking rendered by incising, buffing, and inlaying minerals. Sitting Bull’s signature monarch butterfly is shown fastened to his hat, while the motif flutters across the surface of the horn in bas-relief. For Lakota artist Pourier, the image of Sitting Bull represents Lakota strength and cultural endurance, while butterflies symbolize love and family. The fourth thematic section of the exhibition focuses on the artist as an individual engaged in the process of self-expression while interacting with the rest of the world. Luiseño artist Fritz Scholder (1937-2005) has been called “the most influential, prolific, and controversial figures in the history of Native art.”¹ Through his Super Indians series which he started in 1967, Scholder provided a dramatic counterpoint to the prevailing romantic depictions of Native life. Scholder depicts a Plains warrior wearing stereotypical Native American garb but renders the work in a Pop art color palate dominated by citrus and bubblegum tones in brushstrokes influenced by one of his teachers, painter, Wayne Thiebaud. Far from a placid sunset-infused portrait, this image is fueled by the political radicalism of the 1960s, brimming with energy and immediacy that can barely be contained by the picture frame.

The roots of the Peabody Essex Museum date to the 1799 founding of the East India Marine Society, an organization of Salem captains and supercargoes who had sailed beyond either the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. The society’s charter included a provision for the establishment of a “cabinet of natural and artificial curiosities,” which is what we today would call a museum. Society members brought to Salem a diverse collection of objects from the northwest coast of America, Asia, Africa, Oceania, India and elsewhere. By 1825, the society moved into its own building, East India Marine Hall, which today contains the original display cases and some of the very first objects collected. Salem was also home to the Essex Historical Society (founded in 1821), which celebrated the area’s rich community history, and the Essex County Natural History Society (founded in 1833), which focused on the county’s natural wonders. In 1848, these two organizations merged to form the Essex Institute (the “Essex” in the Peabody Essex Museum’s name). This consolidation brought together extensive and far-ranging collections, including natural specimens, ethnological objects, books and historical memorabilia, all focusing on the area in and around Essex County.In the late 1860s, the Essex Institute refined its mission to the collection and presentation of regional art, history and architecture. In so doing, it transferred its natural history and archaeology collections to the East India Marine Society’s descendent organization, the Peabody Academy of Science (the “Peabody”). In turn, the Peabody, renamed for its great benefactor, the philanthropist George Peabody, transferred its historical collections to the Essex.

In the early 20th century, the Peabody Academy of Science changed its name to the Peabody Museum of Salem and continued to focus on collecting international art and culture. Capitalizing on growing interest in early American architecture and historic preservation, the Essex Institute acquired many important historic houses and was at the forefront of historical interpretation. With their physical proximity, closely connected boards and overlapping collections, the possibility of consolidating the Essex and the Peabody had been discussed over the years. After in-depth studies showed the benefits of such a merger, the consolidation of these two organizations into the new PEM was effected in July 1992. The museum possessed extraordinary collections — more than 840,000 works of art and culture featuring maritime art and history; American art; Asian, Oceanic, and African art; Asian export art; two large libraries with over 400,000 books, manuscripts, and documents; and 22 historic buildings. Today’s collection has grown to include approximately 1 million works and Yin Yu Tang, the only complete Qing Dynasty house outside China.True to the spirit of its past, PEM is dedicated to creating a museum experience that celebrates art and the world in which it was made. By presenting art and culture in new ways, by linking past and present, and by embracing artistic and cultural achievements worldwide, the museum offers unique opportunities to explore a multilayered and interconnected world of creative expression.

Source: www.artknowledgenews.com